By CRISTINA JANNEY

Hays Post

Representatives of judicial districts from across the state gathered in Hays on Tuesday and Wednesday for a mental health summit.

Seventy percent of people who are incarcerated in the United States have a mental illness or substance abuse problem or both.

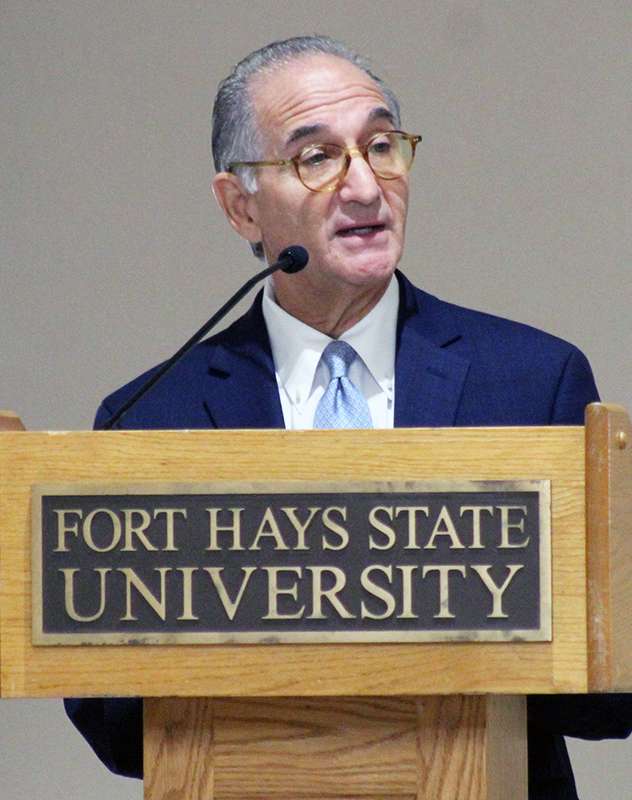

The Hon. Steven Leifman from Florida told the group, "We should create specialty courts for the 30% of people who don't have mental illness or substance abuse."

There are 19 times more people who have mental illnesses in jails and prisons than in civil treatment programs.

He said the people who do have mental illness and substance abuse issues should be placed in therapeutic situations.

Leifman said the United States is failing at dealing with people who have mental illness, and it is costing taxpayers millions of dollars to run a broken system.

The United States has 4% of the world's population and 25% of the incarcerated people, resulting in $1 trillion in direct and indirect costs per year.

Leifman had the opportunity to visit Trieste, Italy, where he said the community is doing it right.

They virtually have no homelessness. They have few, if any, people with serious mental illness in jails. They have few, if any, people with serious mental illness in their forensic hospitals, and they have very few people in their civil hospitals," he said.

Last year, out of 40,000 patients, they only filed 100 cases for civil commitment.

"We do that every day in Miami," he said.

"First, they don't define people by their mental illnesses," he said. "You're not the crazy guy that lives down the street. You are John Smith, who just happens to have a mental illness. Just like you might be John Smith, who just happens to have heart disease or cancer."

When someone has a mental health episode, a doctor immediately goes to that person's home and begins treatment immediately. If the person can't stay at home, they find them housing and assign them three case managers, so they are covered 24 hours until they are stable. They are placed on medication and monitored, but not hospitalized.

As soon as the person begins to recover, they start to try to give them their lives back.

Instead of a state hospital, they have a supportive employment program that includes a radio station, a restaurant and a chic clothing manufacturing operation.

"You walk around the campus, and you don't know the difference between the staff and the patients," he said.

"They have a reason to get up every single day and participate," Leifman said.

"It is a truly remarkable system of care that actually promotes recovery, and there's absolutely no reason why we can't scale that type of system here in the United States. Today, in the United States, we basically do the opposite," he said.

People remain on the streets, sometimes psychotic, for decades.

"We have been so bad about it that the courts have ruled that the way we do it is basically unconstitutional, enormously unsuccessful and enormously expensive without any positive measurable outcomes," he said.

He said the earlier we treat mental illness, the better the outcomes will be.

He called the treatment of people with serious mental illnesses within the judicial system the greatest public policy failure.

"The fact that we have applied the criminal justice model to a disease as opposed to a population health model explains why we have failed so miserably," Leifman said.

Leifman's first experience with the mental health system was when he was 17 and working as an intern for a state senator's office.

He was sent to the state mental hospital to investigate claims that a young man was being mistreated.

He found the man tied in four-point restraints, screaming and moaning and about 100 pounds overweight from being injected with Thorazine.

In reading his file and talking to staff, he learned the young man was not psychotic, but autistic. In the basement, he also saw naked men covered in their own feces being hosed down like they were animals in a zoo.

The state senator's office was able to get the young man with autism placed in a group home. However, thewhat

Eventually, Leifman became a judge in Miami.

The city went from having one wing on one floor of the jail dedicated to people who had mental illness to having three dedicated floors to house people who had mental illness.

"When I became a judge, I had no idea that I was becoming the gatekeeper to the largest psychiatric facility in the state of Florida, the Dade County Jail," he said.

Seventy to 80% of the inmates have a mental health diagnosis and are in immediate need of treatment, he said.

Leifman was eventually given a special assignment to work on mental health issues within the Florida court system. He found the state was spending a third of its mental health budget, $250 million, to restore competency to 2,500 to 3,000 people, when about 160,000 people at the time of their arrest needed acute mental health care and weren't getting it.

After spending so many resources on this small population, either the charges were dropped, they were given credit for time served and were released, or they received probation.

They ended up back on the streets, often psychotic, with no access to treatment, and were sometimes rearrested before they made it out of the parking lot.

Leifman shared the story of Tristan Murphy, who suffered from schizophrenia. He wasn't violent, but had good and bad days, depending on whether he took his medication.

One day, he drove his truck into a pond near the sheriff's office. He was arrested and convicted of felony littering.

He was placed on a work detail while incarcerated. His bunkmates noted he was deteriorating mentally. However, corrections officers continued to give him access to tools, including a chainsaw for his work detail. One day, he took a chainsaw to his neck, ending his life.

Leifman said he was no threat to anyone other than himself. He should never have been arrested. He should have been diverted into treatment, Leifman said.

The governor of Florida, a few weeks ago, signed the Tristin Murphy Act, which expands the Miami mental health diversion program statewide.

"We shouldn't need that kind of horror to get the attention of policymakers," he said, "because we all know that the way we handle individuals with these illnesses is wrong and doesn't really work."

He said people who have mental illnesses are less dangerous than the general population and a lot less dangerous than the general population when they are on medication. They are more likely to be the victims of violent crime than the perpetrators.

"We also know that recovery rates for people with mental illness, in many cases, are much better than heart disease and diabetes," Leifman said. "These are not terminal illnesses. They are treatable illnesses."

People with schizophrenia have higher rates of heart disease and cancer because untreated schizophrenia results in a depletion of the brain chemical dopamine.

They feel awful, Leifman said, so they often chain smoke because the nicotine helps cognition and helps them feel better.

When these people end up in jail, not only do taxpayers have to pay for treatment of the mental illness, but also severe physical health concerns as a result of the mental illness going untreated, Leifman said.

"The good news is that this is a very fixable system," he said.

The judicial system and mental health systems were developed when the most acutely ill were still in state hospitals. The community mental health systems were designed to handle people who have moderate mental illness, Leifman said.

The hospitals were shut down. The U.S. adopted the war on crime and sentencing guidelines and drastically cut funds for low-income housing, and the population of the acute mentally ill was thrown into communities that were not prepared for them, he said.

"Instead of blaming themselves for not developing an appropriate system of care, we end up blaming this population, and we use the justice system to punish them, and that has not worked out too well," Leifman said.

He said our society would never allow people to be treated in primary care as we treat people with mental illnesses.

"If you threw people who had primary care illnesses out of hospitals in the middle of the night like we do people with mental illnesses, you'd get arrested," he said.

Leifman said this is a national issue that needs national money, but the solutions can start at the local level.

"Each community needs to take a good, hard look at how they are doing things, and develop collaborative agreements to alter and restructure how we approach this population," he said.

Miami put to gether a two-part approach, pre-arrest and post-arrest.

This included Crisis Intervention Teams, which include specially trained law enforcement officers to respond when someone is having a mental health episode. This often has resulted in people being diverted into treatment instead of arrest

In 10 years, two Crisis Intervention Teams responded to more than 105,000 calls and made fewer than 200 arrests.

Overall arrests plummeted. Dade County closed one of its jails, saving $168 million. Police shootings almost stopped.

The post-arrest program eliminated many of the time-consuming competency evaluations in favor of bringing these individuals into treatment as soon as possible.

Assisted Outpatient Treatment programs were created, also known as AOT. Hays has had an AOT program since 2022.

SEE RELATED STORY: Ellis County mental health court pilot sees success in first year.

And peers were enlisted to help people navigate the system and encourage work toward recovery.

Recidivism rates for misdemeanor cases decreased from 75% to 20% for individuals participating in these programs. The treatment model proved so effective that it was expanded to include nonviolent felony cases. Recidivism rates decreased from 75% to 6%.

Continuing care was still needed for individuals with the most acute illnesses, so Dade County recently passed a bond issue to build a facility for these individuals based on the Trieste model.

It offers wrap-around services, including crisis stabilization, primary care, a dental clinic, a podiatry clinic, an eye clinic, short-term residential care, tattoo removal, a day program, a supportive employment program, a computer lab, a GED program, and a courtroom that can handle both civil and criminal cases onsite.

"Not one person, not one party, not one institution created this mess. Not one person, party or institution will fix it. It takes all of us in this room to start looking at our systems and determine how there is a better way to run this system," Leifman said.